|

Nihontocraft - Japanese Sword Question and Answer Archive

Verison 2 July 2016

Q: I am a beginner trying to understand what are "ware" and when to avoid them. Could you tell about "ware" in general and how they affect the desirability of blades?

A: Lamination openings are called kitae ware. My mentors have taught me some basic guide lines about how to view them. I will be glad to share them with you.

First: Kitae ware can be found on all levels of swords, up to and beyond the Juyo level.

Second: Kitae ware are more of a problem for our eyes than for the sword. They do not hinder the purpose of the blade (I.E. cut well, don't bend, don't break) with the exception of my third point.

Third: Blades with kitae ware in the ha or boshi could be bad for the function of the blade. This is were the impact of the cutting blow hits the blade the hardest and a lamination opening near the edge could become a crack in actual use. These should be avoided as a general rule. A deep mune ware is also a problem for function.

Fourth: Kitae ware in the ji do not effect the function of the blade but they have "visual weight" that bothers the eye. A blade with a kitae ware in the ji is normally priced lower than a comparable blade that does not have a kitae ware in the ji.

Fifth: Kitae ware in the shinogi-ji are a non-issue unless they are frequent or large.

Sixth: Kitae ware are often found in koto blades. As long as the are not frequent, large or located in the ha or boshi - they are not a problem in the view of most collectors.

Seventh: As a rule of collecting, Kitae ware in the ji of shinto or shin-shinto are not desirable. Small kitae ware in the shinogi-ji of shinto or shin-shinto are a non-issue. Gendatio need to be perfect. This is a rule based on cosmetic standards, not function.

Q: I am a beginner trying to understand what is involved in buying a good sword. I would like to study and learn from the sword. Also, I want to acquire it as an investment. How do I start?

A: The study of Nihonto is a wonderful and endless endeavor. It is a joy to meet those who are setting foot on the path.

Please attend as many sword study group meetings and shows as you can. Look at many blades and network with other collectors. There are shows all over the US every year.

Please invest in many sword reference books.

Doing these things first, before you ever buy a sword, is the best approach.

When you are ready to shop for a blade:

The basic rules of buying are to seek blades that are: ubu, healthy, signed, representative/typical work for the smith, high quality work, high quality polish and papered. This is the highest goal one can set. But this is not always possible or necessary. Osuriage mumei koto and even suriage zaimei shinto / shinshinto can be great to own in some cases. Many people would be perfectly happy with a suriage partial mei shodai Tadayoshi or suriage partial mei Koyama Munetsugu because of the cost involved to acquire an ubu zaimei example. This also depends on one's study goals and budget. In any case, quality and health should not be sacrificed.

It is not recommended to use Nihonto collecting as a way of investment. The price of Nihonto has a lot to do with the economy in Japan and one just cannot predict what the future is going to be in the world economy. The investment minded beginner is normally at the show or on the internet looking at out-of-polish, unpapered blades trying to find the "jewel". This is where people make mistakes. The beginning of one's involvement in Nihonto is normally not a time when people have enough knowledge to identify a diamond in the rough. The knowledge and enjoyment that one gets from owning a nice blade is the tangible profit. The key is to buy the best one that you can afford and focus on papered, signed, ubu, healthy, high quality items. These are the items that tend to hold their value.

Q: Are gendai worth collecting? They seem to command about the same price as some older blades.

A: Many people like gendai because they are all very healthy, if not abused and there is little chance of a fake mei. It is kind of a "safe zone" to some collectors. The main reason to like gendai is that the best ones are often very high quality. There are several gendai makers that are highly ranked and their work can and should command a high price. However, others may prefer a blade that a Samurai owned and used. The aura of that is an important part of their appreciation. Choosing between a gendai or an old blade is a matter of personal preference. Quality and health are the biggest points to study.

Q: How can I determine what a good price is for a blade?

To establish if a blade has a reasonable price or not, one has to compare similar blades by similar rank and school smiths in the current market. This can be tricky. There are many parameters of appreciation that may seem small, but effect price significantly. For example if one is comparing two blades by the same maker to establish market value, be sure they are really comparable. If one of the blades is not the smith's typical work style, machi-o-kuri and has a slender mihaba, it may be worth only a fraction of a blade by the same smith that is a text-book, ubu and normal mihaba example. Also, a kobo saku (shop made) blade vs a jishin saku (smith made by himself) blade makes a large difference in price. Here is a caveat to consider: All four hypothetical blades mentioned in the paragraph could have the same level paper.

Q: I am shopping on the net and having a hard time choosing from these two blades. Would you rather have a Tadahiro wakizashi who is a Jo Jo Saku rated smith, or katana by Tsuguhira who is a Chu Jo Saku rated smith?

A: Both could be very nice. Some people would say, go with the one that "speaks" to you. However, it can be hard to judge that from photos. Be sure that in either case, you are allowed an inspection period. No matter how good the blade looks in photos, you cannot know the blade for sure until it is in your hands.

The ranking of smiths cannot be applied reliably to all of their works. Every smith had good days and bad days. A bigger factor is that there are jishin saku (works made wholly by the smith) and kobo saku (shop / assistant made works with the mei of the master). Of course, these are both "real" and will get a Hozon paper or better, but the difference in quality and price is huge. It's good to remain aware of the rankings but let the blade speak for itself. One can find many chu and chu jo saku level works that are superior and some Jo saku level works that disappoint.

Compare the health and quality of the blades. Heath and quality are the most important things. They are above "rank".

Q: How does one know when to avoid a blade with small ware or when it's ok for a blade to have one?

There are times when a blade that has a kitae ware should be avoided. The parameters of this are directly related to the function of the sword, not aesthetics. A large ware in the ha or boshi could cause a big hakobori or fast spreading crack in a fight. This could be a life or death difference for the wielder. This is where a concern of ware comes from. Small or linear ware in the ji or shinogi-ji are not a problem for function. The shinogi-ji is the most forgivable place to have a ware. A significant ware on the mune can be an issue because of defensive moves using the mune to block. Also, a significant mune ware can be a problem for offense. A blade can split along the mune from strong force on the the ha if there is a bad mune ware.

Here is where the "grey area" comes in. It is always "looming" in our hobby. There are times when a minor ware, even in a bad location, can be forgiven. Let's talk about a few of these exceptions. A blade of high empirical value may still be very desirable even with a ware. An example of this would be a blade with an ubu singed nakago. This is especially true for singed and dated works as well as signed koto blades. Hada-mono blades by even master smiths can have minor ware. We have seen several Hankei, Kiyomaru and many rare koto works over the years that have a ware that can be ignored. Blades with masame hada often have some linear so-called "masaware" This is absolutely fine if minor.

The control and consistency of a blade's nioi-guchi and the even tempering of a blade's jigane are the two factors that show the quality (cutting well and being durable) of the blade the most. A model of appreciation that is based on the function of the sword as a weapon is what we should aspire to.

A safe zone ware (ji or shinogi-ji) that has enough visual weight to be distracting will lower the price of a blade. But its really mostly a problem for our eyes, not so much a problem for the weapon in terms of its function.

Calligraphy and painting were meant to be done perfectly in appearance but we accept the imperfections that result from the artist's creation process as part of an overall appreciation. When we look at a sword, I think we should have a similar mindset. A sword was meant to be made as a perfect edged weapon not a perfect object visually. Therefore, any imperfection does not depreciate the sword's value as a weapon as long as it has no impact on its function.

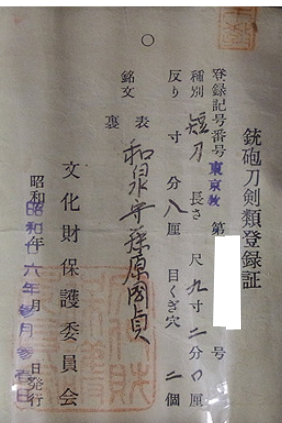

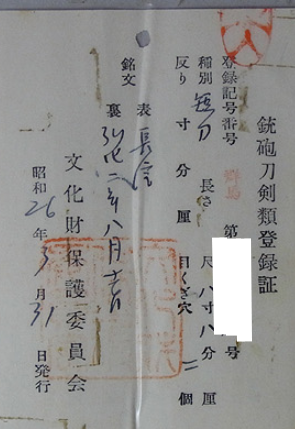

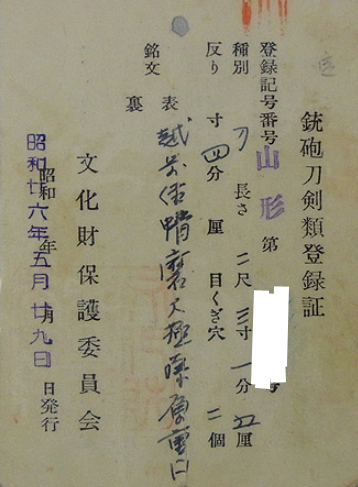

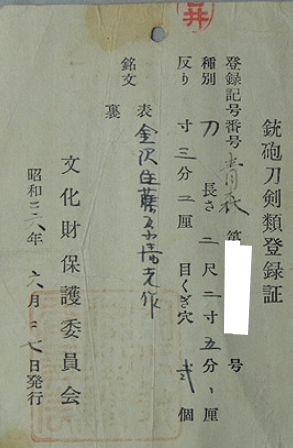

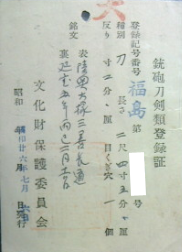

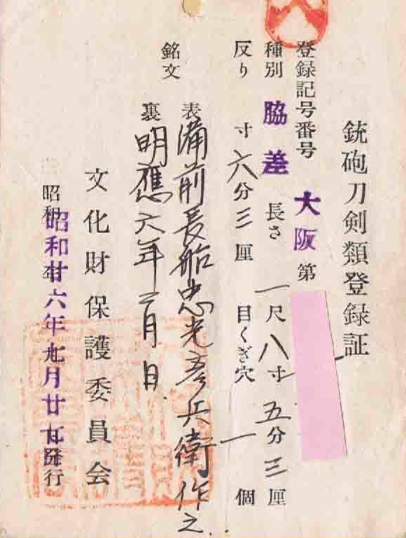

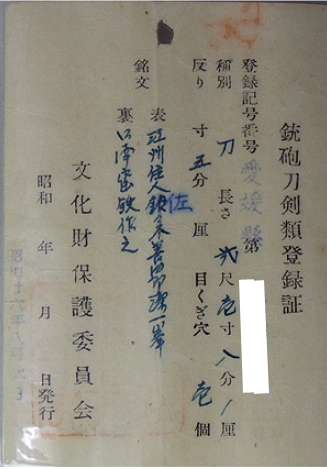

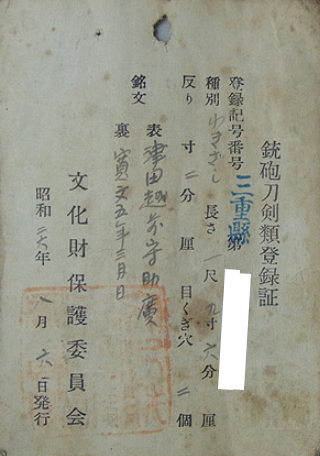

Q: Are blades with a Torokusho date of Showa 26 (1951) ones that came from top Daimyo collections? I have heard that only the treasured items like Masamune, Ichimonji, Sanjo Munechika, Awataguchi, Rai etc... from only old important families were invited / allowed to get registered in Showa 26 - 27.

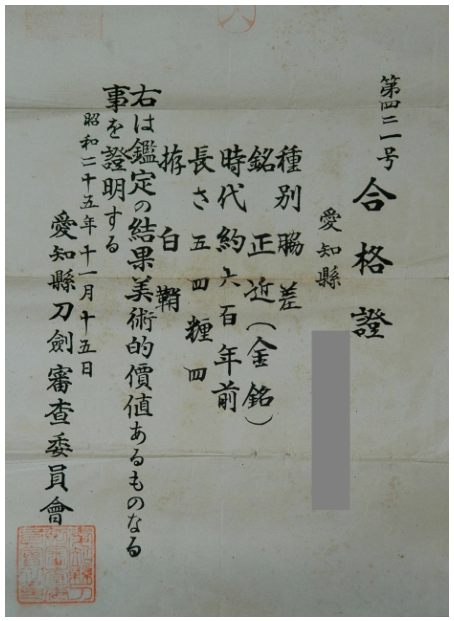

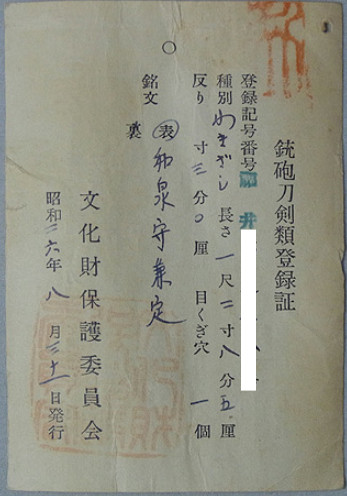

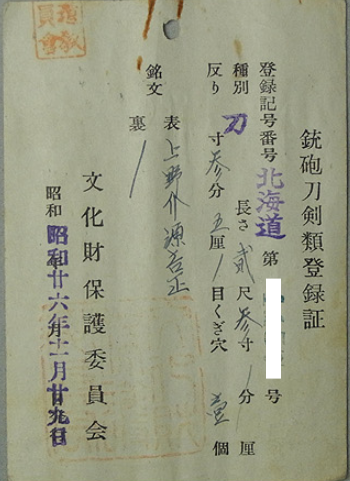

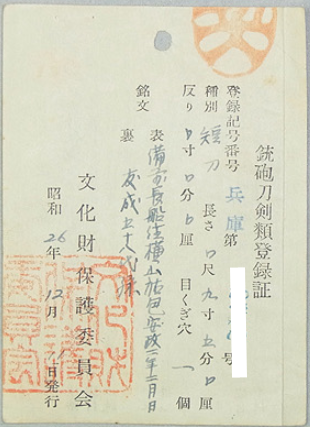

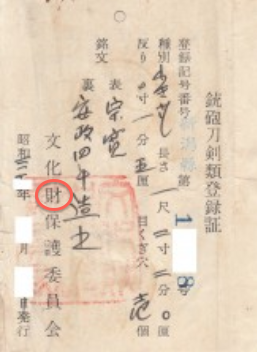

You are asking about the phrase of so-called "Daimyo/Kazoku" Torokusho registration some dealers/collectors like to use. This registration was based on the Culture Property Protection Law. Any swords that had artistic value could be registered. Even gimei and blades with any kind of kizu could be registered. This was not a shinsa. The fee was 230 Yen. This was established on Nov. 15 of Showa 25 and executed on Dec. 1, Showa 25.

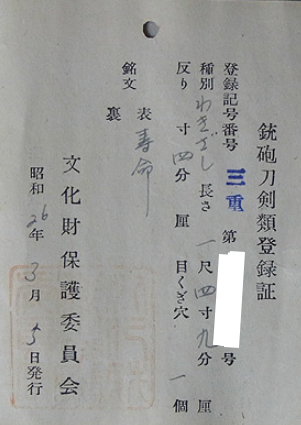

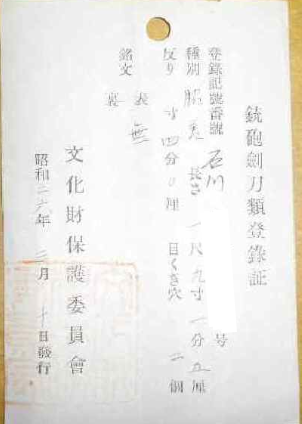

There is the factor that people in "the know" and in charge of important collections, would have been more aware of this new law than others and quick to react. But there is no evidence of special or private access. Please remember that at this time in sword history the total destruction of Nihonto was just barely avoided. Regular class people with regular class family treasures wanted them to be protected just as much as Shrines and Daimyos. Please see the collection of Showa 26 registration cards here (below). These are all regular class items. Yes, there were many meibutsu Daimyo/Shrine blades registered in 1951 but these years were not times when blades of that level were exclusively invited or permitted.

Showa 25 11 15 (first day) Aichi Prefecture Mihara Masachika Kinpun mei

Showa 26 03 05 Mie Prefecture Jumyo

Showa 26 03 10 Ishikawa Prefecture mumei

Showa 26 03 31 02 Tokyo Izumi No Kami Kunisada

Showa 26 03 31 03 Gunma Prefecture Naganobu

Showa 26 05 29 Yamagata Prefecture Shige xx(cut)

Showa 26 06 27 Aomori Prefecture Kaga Kiyomitsu

Showa 26 07 06 Fukushima Prefecture Nagamichi

Showa 26 07 27 Osaka Tadamitsu Hikobe

Showa 26 08 02 Ehime Prefecture Sasaki Ippo

Showa 26 08 06 Mie Prefecture Tsuda Sukehiro

Showa 26 08 31 Fukui Prefecture Kanesada

Showa 26 11 29 Hokkaido Yoshimasa

Showa 26 12 11 Hyoago Prefecture Bizen Yokoyama Sukekane

Showa 26 Niigata Prefecture Soken

|