|

Important Intangible Cultural Property

of Japan's Prefecture Level

Published with the author's permission and including updated information

Introduction The Samurai class was eliminated after the

Meiji Restoration. Traditional ways of making swords, Nihonto, became

unnecessary in a soon-to-be modern society. To ensure social stability and

to put Japan on a fast track to westernization,the Japanese government advised the Samurai class to abandon their swords and hair styles in Meiji 4, 1871, and eventually prohibited wearing swords in Meiji 9, 1876. Many sword smiths lost their jobs and had to find other trades to make their living. In order to preserve the traditional Japanese art and

craft not to be lost or forgotten in the modernized Japan, the System of

Imperial Arts and Crafts Experts, 帝室技芸員の制度, was established in Meiji 23, 1890 by

the Meiji Emperor and his government. Gassan Sadakazu 月山貞一 and Miyamoto

Kanenori 宮本包則 were designated as Teishitsu Gigeiin, 帝室技芸員, together with five

other artists and artisans from other fields in Meiji 39, 1906. They were the first and the last sword smiths honored with this title. The modernization of

Japan also accelerated Japan's invasion into the adjacent countries.

Japan's military machine was at full speed between 1894 and 1945. The

military minded Japanese army promoted the use of the samurai swords as an officers' side arm. Making

samurai swords or Nihonto was not only revived it was at an all time high.

With Army and Navy having their own sword manufacturing facilities and many

other privately running sword-making shops, preservation of Nihonto was not a

concern anymore. This may explain the fact that in the period from 1890 to 1945, in which the Teishitsu Gigeiin system was functioning, only two sword smiths, Sadakazu and Kanenori, were appointed to Teishitsu Gigeiin, while a total of seventy seven artists and craftsmen appointed from other fields. Sadakazu and Kanenori died Taisho 7, 1919, and Taisho 15, 1926, respectively, but no other sword smiths were appointed to succeed them.

After

WWII, the Occupation Force in Japan stopped all sword-making activities.

Sword preservation was also difficult if not impossible during that time.

However, Nihonto enthusiasts were able to persuade the Occupation Force to

change their views towards these edged weapons. These aren't merely weapons, some of them are valuable objects of art. Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai, NBTHK, was

established in Showa 23, 1948 as a result of the effort of Kazan Sato and Honma

Junji in promoting sword preservation with the concept of Art Sword. When

this view was recognized and accepted by the Occupation Force, making Nihonto

was once again allowed. Japan Cultural Property Preservation Committee

issued sword-making permits to qualified smiths in Showa 28, 1953.

According to a survey conducted in Showa 45, there were 320 qualified smiths

with working permits at that time. This Japanese cultural heritage was

finally saved. To support

preservation and inheritance of important art performances and craftsman's

techniques of Japanese tradition, the system of Important Intangible Cultural

Property重要無形文化財 was initiated and established in Showa 29, 1954 by the Japanese

government. This is the highest level of recognition a living Japanese

artist or artisan could receive. Individuals holding this title are also known

as living National Treasures, Ningen Kokuho人間国宝. The Agency for Cultural

Affairs, a division of Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and

Technology of Japanese government, is responsible for selection and awarding of

this title. Among about 150 individuals so far awarded with the Ningen

Kokuho title in the craftsman fields, six are outstanding sword smiths.

They are Takahashi Sadatsugu 高橋貞次awarded in Showa 32, Miyairi Yukihira 宮入行平in

Showa 38, Gassan Sadakazu 月山貞一in Showa 46, Sumitani Masamine 隅谷正峰in Showa 56,

Amata Akitsugu 天田昭次in Heisei 9, 1997, and Osumi Toshihira 大隈俊平in Heisei 9.

The last two smiths are still active, while other four have passed away.

These smiths are well known to Nihonto enthusiasts in Japan and around the

world. In addition to the Living National Treasure,

there is another level of recognition that is lesser known to collectors outside

of Japan. It is the Prefecture level of Important Intangible Cultural

Property. The achievement and merit of individual artists or artisans were

evaluated and honored by the Cultural Property Office of the Prefecture

Government. Different Prefectures might have different sets of criteria in

the evaluation process. It is not equivalent to the national level and is

not a pre-requisite for an artist or artisan to obtain before being considered

for the Living National Treasure. There have been many

smiths received this Prefecture level of recognition since the end of

WWII. This article focuses on the six who were active during the

War. These six smiths were referred in Tokuno Kazuo's Tokotaikan, and

because this book was published in 1977, all six smiths received

this title before 1977. They are Ishii Akifusa 石井昭房of Chiba Prefecture,

Niwa Kanenobu 丹波兼延 of Gifu Prefecture, Imaizumi Toshimitsu 今泉俊光of Okayama

Prefecture, Kojima Nagatoshi 小島長寿in Tokushima Prefecture, Takahashi Nobufusa

高橋信房 of Miyagi Prefecture, and Kawashima Tadayoshi 川島忠善of Shimane

Prefecture. The following is a brief description of the work style of

them.

Sword-smiths Akifusa昭房: Awa-no

Kuni Akifusa. He was born in Meiji 42, became a student of Kurihara

Hikosaburo Akihide栗原彦三郎昭秀 in Showa 9, received an award in the Shinsakuto

contest held in Showa 11, became an instructor in Akihide's Nihonto Tanren

Denshusho in Showa 12, designated as Tateyama city Intangible Cultural

Property館山市無形文化財 in Showa 32, and Chiba Prefecture Intangible Cultural

Property千葉県無形文化財 in Showa 37. He worked in the tradition of Kamakura

Ichimonji Sukezane with gunome midare and choji midare hamon.

Kanenobu 兼延: Noshu ju Niwa Kanenobu

濃州住丹波兼延. He was born in April of Meiji 36, the second son of Kanenobu

兼信. He started to learn Nihonto-making from his father at age 12. He

was also an excellent engraver. His work styles are ko-itame with strong

ji-nie, wide suguha and ko-notare with ko-nie. He worked for the Japanese

Army during WWII and was designated as Important Intangible Cultural Property of

Gifu Prefecture 岐阜県重要無形文化財 in November of Showa 48. Toshimitsu

俊光: Bizen-no Kuni Osafune Ju Fujiwara Toshimitsu. He was born in Meiji

31, a self-taught smith in Bizen and Soden Bizen tradition, specializing in

choji-midare hamon. He worked for the Japanese Army during WWII and was

designated as Okayama Prefecture Important Intangible Cultural Property

岡山県重要無形文化財 in the March of Showa 29. In Showa 45 he received the title of

Mukansa. Nagatoshi 長寿: Seishinshi Nagatoshi, Seishinshi

Nagatoshi Saku (kao). Nagatoshi's original name was Kojima Tamekazu

小島為一. He was born in Meiji 34, 1901 and learned sword-making from his

father Kojima Tomoro Kunitomo 小島友郎國友 and older brother Genbusai Shigefusa 玄武斎重房.

He started making swords in Showa 8 and focused on the Bizen tradition

especially the style of Osafune Nagamitsu 長船長光. Nioi based choji hamon

with long ashi and well-forged mokume hada with frosty ji-nie are the main

characteristics of his work. He was contracted to work for the Japanese

Army at the Osaka arsenal in Showa 16, and in Showa 49, 1974, he was designated

as the Important Intangible Cultural Property by the Tokushima Prefecture

Government 徳島県重要無形文化財 for his contribution of over forty years of

sword-making. Nobufusa 信房: Hokke Saburo

Nobufusa 法華三郎信房. He was born in May of Meiji 42 as

the eighth generation Nobufusa. The first generation Nobufusa was a

student of the ninth generation Sendai Kunikane. This line of smiths has

been working in the Yamato tradition. He learned how to make Nihonto from

his father in both Bizen and Yamato. He liked the Yamato Hosho style and

spent a lot of effort in learning and recreating works of Yamato traditions,

especially the style of Shodai Yamashiro Daijo Kunikane. He was designated

as Miyagi Prefecture Important Intangible Cultural Property 宮城県重要無形文化財 in

December 6th Showa 41. Tadayoshi 忠善: His name is Kawashima

Shin, son of Kawashima Zaemon. He was born on August 15th of Taisho 12, 1923 in

Shimane Prefecture. He learned making Nihonto from his father with a focus on

Bizen tradition especially the workmanship of Nagamitsu. He participated

in the sixth Nihonto Shinsakuto exhibition in Showa 16, 1941, at age

eighteen. He was designated as Important Intangible Culture Property in

May of Showa 41, 1966 by the Shimane Prefecture Government, 島根県重要無形文化財.

Comparison Tokotaikan is one of the few books providing ratings to a large group of gendai smiths together with smiths of earlier times. Note that all ratings in Tokotaikan are those as of 1977. The "number of million Yen" system was used to give indications of how well one smith compares to another. The entry-level rating appears to be 1 million Yen. Most gendai smiths were ranked at this level. Higher ends of the spectrum are ratings of 35 or 30 million Yen for smiths from Ko-Bizen, Awataguchi, and the like. The four smiths who received Ningen Kokuho title before 1977, as well as a non-recipient Tsukamoto Okimasa, are all rated 3.5 million Yen in Tokotaikan. This seems low but it's the highest ranking given to gendai smith in the book. The ratings of smiths honored at the Prefecture level are 2.8 million Yen for Toshimitsu, 2.5 million Yen for Nagatoshi, Nobufusa, and Tadayoshi, and 2 million Yen for Akifusa and Kanenobu. For a quick comparison, some of the better known smiths like Kasama Shigetsugu, Kurihara Akihide, and Ozawa Masatoshi were rated at 2.5, 1.5 and 2.2 million yen, respectively, in Tokotaikan. The rating for Kurihara Akihide, 1.5 million Yen, is surprisingly low. His reputation that he was rather a politician than a sword smith had overshadowed his image for a few decades after the war. It has been changing in the last ten years.

The author would like

to point out that the ratings in Tokotaikan should be viewed as general

guidelines, not as an absolute quality scale for sword evaluation. The workmanship in blades of a smith varied greatly during WWII. Some smiths may have

made good quality blades but were never recorded in any Meikan for one reason or

another. This doesn't mean their works are not worthy of collecting.

Therefore, each blade should be studied, evaluated, and appreciated by its own

merit and historical background, not by a set of numbers or ratings in a

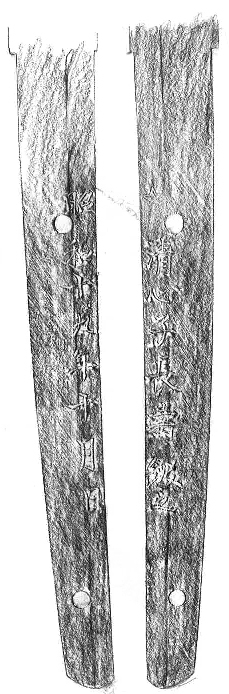

book. The Study

Piece Sugata: Shinoji-zukuri, koshi-zori, 25

3/4" nagasa, 3/5" sori,

normal high mune and shinogi, niku present Kissaki:

Chu kissaki Boshi:

Midare-komi with little turn back in

nioi Hamon: Nioi based long ashi choji and

gunome mixed with midare Ji-hada: Ko-itame and

mokume with frosty ji-nie, running itame in

shinogi-ji Nakago: 8 1/2", ubu, two mekugi-ana,

signed and dated tachi-mei, Star stamp on omote, keisho style file

marks Omote: 清心子長寿鍜之 Ura: 昭和十九年十月日 Koshirae:

1944 Japanese Army Officer's mounts, sometimes referred to

as landing forces mounts The surfaces and outlines of the blade are

flat and straight giving the indication of a good polish. But, details within

the hada are hard to see due to scratch marks left on the surface of the ji. It

looks like the polisher skipped couple finer stones. The hamon is

nioi based choji-midare with long ashi. On the omote, the hamon starts as gunome

from the hamachi, turns into (almost) sugu with ashi for a couple of inches,

then changs into choji with long ashi for the rest of its length. On the

ura, the hamon starts as midare from the hamachi and changes into

long-ashi-choji at the same location as does the omote side. At the

transition point, the hamon takes a dive to the edge of the blade on both sides,

then comes back as choji on both sides. At first glance, this seems to be

just another run-of-the-mill gendaito. Upon closer examination, the beauty

of the workmanship is revealed. The shallow koshizori curvature with

chu-kissaki and niku give a strong and balanced feel. The design of the

hamon is interesting and the hada is very well forged. Nagatoshi was 43

years old when he made this blade.

References:

References: 1. Tokotaikan,

Tokunou Kazuo 2. Nihonto Kantei Hitsukei, Fukunaga Suiken 3. Gendai Toko

Meikan, Oono Tadashi 4. Nihonto Jiten, Fujishiro Yoshio 5. Nihonto Kantei

Dokuhon, Nagayama Kokan 6. Nihon no Katana, Tokyo National Museum 7. The

Gassan Tradition, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 8. Jun-ichi Uoshima, Tokushima

Prefectural Museum 9. Kenji Mishina, personal

communication. |